Anika Kowalik

Anika Kowalik bore roots in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and completed a BFA in Printmaking at Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design in 2017. Kowalik’s current practice channels personal experiences as a young black femme to explore the depths of institutionalized racist ideology, ancestry, and the coming of age to create works that record their own history. As a person who is a part of a marginalized group, it is vital to unpack the truth through many facets of documentation. Kowalik finds it easier to communicate these personal experiences through materiality, expanding beyond the physical body we commonly search for. Kowalik recently completed their first Artist-In-Residence at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in April 2021.

Photo by Anika Kowalik

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose was to exhibit work amongst a cohort of Black women/femme artists to give perspective on the lack of representation within art institutions in Wisconsin. The events leading up to, during and after the exhibition showed how crucial it is for Black women/femme’s work to be within those spaces. The work is constantly being disregarded, overlooked and devalued by institutions and their supporters. MMoCA’s director, Christina, has proven that the pawns of white supremacy stop at nothing to protect the very system that benefits them. All while, violently silencing those who’s perspectives they need to create cultural context and engagement for capital.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The show highlighted how Black women and femmes are easily exploited under the radar. The insidious tactics used to muzzle us vary from micro aggressive behavior to blanatant outright racism with no means to triage or hold those who have committed harm accountable. You simply do not care. It’s evident.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

The stress is immeasurable, as all artists and their work is susceptible to being vandalized without consequence under the watch of MMoCA. My 1 of 2 works is not on display due to poor management of this situation.

Blanche Brown

Blanche Brown is an art therapist and marriage and family therapist who believes in the power of art to heal. Brown is an art and community activist whose work addresses social injustices and the psychological and psychosocial impact these issues have on underserved and underrepresented groups. Her artwork provides a forum for youth, women, minorities, and diverse individuals to openly discuss the challenges they encounter. As a professional artist for over 20 years, Brown has exhibited both locally and nationally and has been a guest artist and artist-in-residence at several schools and community programs.

Photo by Fatima Laster

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose for participating in the show was to celebrate the beauty, tenacity, strength, and resiliency through a lasting legacy left by my ancestors. My small artistic voice added to those of my fellow artists would ring out loudly despite a history of blood, sweat, and tears.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

One thing the show highlighted for me was the beauty of collaboration through the unique experiences of a sisterhood of like-minded creatives whose contributions would be manifested in history long after the exhibition was over.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

I’m not sure if I have the words—I will say that in a time when the weather report continues to remain bleak for a favorable outcome I have been painfully reminded (again) that racism still finds a way to make its ugly and wicked mark on the oppressed.

Chrystal Gillon-Mabry

Chrystal Gillon-Mabry is a visual artist who grew up in a creative and resourceful home where she was encouraged to use her innate ability to “make things.” She graduated with a BA in art education from Alverno College, and later received a BFA from the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. Gillon couples her fine arts training with self-taught skills and has been working in collage, mixed media, and assemblage for a number of years. She uses a variety of mediums mixed with found and recycled objects as she explores themes from the perspective and experiences of an African-American woman, as a follower of Jesus, and as expressions of nostalgia. She was an artist-in-residence at the Mandel Creative Group Plaid Tuba Art Studio and was honored as a recipient of the Sisters of Creativity.

Photo by Lila Aryan

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

I wanted to participate in the Ain’t I A Woman show for a number of reasons. The first being because I so appreciated the honor of being invited by Fatima, a person I respect and wish to support in her endeavors. She has a level head and greatly respects the artists she works with – being their advocate and looking out for their best interest. I want to honor her trustworthiness and the fact that she trusts my work to be included in this 1st time opportunity for her.

Second, this exhibition would be a positive challenge for me. A challenge for me to step out into a different venue with a different audience – MMoCA being an organization with notoriety, with an audience having a reputation of being progressive.

Third, after reading the Bell Hooks book and familiarizing myself with Sojourner Truth’s speech, I felt the content from both women a provocation to take on a personal dare to create work that would and could reflect the injustices society has done to black women and girls and counter that with visual statements of empowerment through my work.

Last, it creates documentation and legacy of my place as an African-American artist.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

On a positive note, for me, the show highlighted the beauty and power that a group of black women can bring into an arena and command being noticed and applauded for their sheer talent. I acknowledge that I felt supremely pampered which I now see and attribute to Fatima’s efforts and desire to care for the artists she asked to be a part of this investment and her desire to make a strong statement on and for black women and girls.

It also highlighted the irony of having the thesis of the show, the grievance of injury and wrong toward black women, being played out in real time in the institution that was supposedly supportive and embracing the diversity platform of the exhibition’s title.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

The actual participation in the exhibition – the opening and the presence in the museum – has not been a bad experience in and of itself. However, being put in the position of having to concern myself with defending myself, my sista’s, and our work has been more than an annoyance. It is exhausting emotionally and an energy drain to my spirit. It has been consuming time I really need to dedicate to other concerns. It has caused concern for the safety of my work from assault and the well-being of a fellow sister who has been assaulted more than once and who is in a vulnerable place and can’t, at this time, defend herself.

It makes me angry that the devaluation, inconsideration, and the attitude that we as a black women can still and again be used to reflect an institution’s hypocritical guise and profession of inclusiveness.

Emily Leach

Emily Leach’s creative practice and research focuses on blackness, bodies, (re)production, growth, and language. Leach studies glass to consider the philosophies and strategies of optics. She has exhibited locally and nationally, and her work has been published in New Glass Review and Gumbo Magazine. Leach was a semi-finalist for the Forward Art Prize for visual artists in Dane County in 2019 and 2020. She was also recognized as one of the Madison Bridge Work Emerging Artists (2019-20) through Arts + Literature Laboratory.

Photo by Ken Flanagan

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

The theme of the exhibition, “Ain’t I A Woman?”, invites challenging and vulnerable artwork. I was compelled by the historic magnitude: this would be the first Wisconsin Triennial to focus on Black women, femmes and GNC folk — explicitly in recognition of the repeated exclusion of Black women from historical acknowledgement. This would be the first guest curated exhibition, perhaps acknowledging the implicit bias of the institution.

I was honored to be invited to the Wisconsin Triennial. Even still, accepting the invitation was an act of good faith and extension of trust. I was uncertain that the museum would be able to meaningfully care for the artists and our work through context, programming and security.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

I am still processing what the show has meant to me. There are many threads: solidarity, gratitude, and pride, which are interwoven with anxiety, anger and disappointment. My work in the Triennial is in collaboration with my mother, my grandmother, and my ancestors. I am thankful that my work could be seen in the context of this collective and am moved by the common themes that I see in our work. I am grateful to connect with the other incredible artists in this exhibition.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

To be clear, I am upset by: the negligence that made this vandalism and theft possible; and the lack of accountability and public response from the museum. Together, these represent a major breach of trust for the exhibited artists; failure to standardize care for the artwork in the museum’s possession; and neglected responsibility to the community the museum serves.

As of this writing, the last communication that the Wisconsin Triennial artists received directly from museum leadership was on Thursday, July 7. All communications have stressed the need to handle this crisis internally, and have encouraged artists to reach out to museum leadership individually. To my knowledge, there has been no private or public acknowledgement that the museum’s silence has been misguided or actively harmful.

I am insulted and astonished that the leadership of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art would ask for good faith, understanding and composure from a group of Black artists which ostensibly acknowledges have been harmed, minoritized, and disenfranchised by the very state and institutions that it represents. When an institution has lost trust, it must rebuild confidence through direct, tangible and overt action.

Since the end of June, the artists in the Triennial have been working diligently to find time to meet collectively, process together, and deliberate on responses and desired outcomes. This has been a traumatic and exhausting experience. I am genuinely surprised and disappointed that the museum has not proactively offered any structure to support healing and amends (especially since the museum made these efforts following the assault in March.) I am angry, I am tired, I am dispirited and I am heartbroken.

Joya Jean

Joya Jean was born in Chicago, Illinois. Raised in a house with five other women, including her grandmother, the experience had a major impact on her creative drive, and it embedded the distinguished images that she reflects in her art. With fine art and braiding both being a passion for Jean, she began to experiment with incorporating hair as a medium in her practice. Integrating braided material quickly became more of a ritual, adding new meaning in her work. She has also dabbled in numerous mediums and materials, including wood/furniture-making, interior designing, sculpture work, and painting. Jean graduated from the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design with a BFA and a minor in interior architectural design.

Photo by Anamarie Watson

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

The purpose of participating in this show for me was to be a part of a collective group of powerful, Black creative queens. To take up space and celebrate why we matter.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The Show highlighted black women being honored and recognized for our accomplishments, our wants, our needs. How black women can be a threat in numbers, and turn a whole room out.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

Stressful, disgusted, embarrassed, but surprisingly not surprised by this typical behavior and white supremacy attitude toward black women the moment we walk in. We have been a threat to this society since the beginning of time. It’s like they always wanna see us down and hopeless. You really can’t trust white people no matter how much things change because the system will remain the same. Racist!! Black business will grow!!

Kierston Ghaznavi

Kierston Ghaznavi is an illustrator and artist, both traditional and digital. Her vibrantly-colored and articulated paper and wooden dolls depict the beauty and unique personalities of Black women today. In addition, the artist’s work incorporates Black pop culture, Afrocentric themes, natural hair, affirmations of self-love, and plus-size body appreciation. Ghaznavi earned her BFA in Graphic Design from the Peck School of the Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her work has been in numerous exhibitions in Southeastern Wisconsin, including Represent at the Racine Art Museum, This is America at 5 Points Art Gallery + Studios, and 30x30x30 at Var Gallery in Milwaukee.

Photo by Aaron Vivian

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose in participating in the show: I was excited to celebrate this historic moment with Fatima who curated a meaningful show including some Incredible black femme/GNC artists; who all deserved this platform and opportunity to showcase our experience as such in America, the trials, pain but also the joy and magic. It was an opportunity for me to challenge myself as an artist; bringing my best work to this exhibition.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

This show highlighted sisterhood and community. It allowed the artists to express the phrase “Ain’t I a Woman?” meant to them. It was healing to see the uplifting of our ancestors through our visual mediums of choice. It showed the multifaceted views of the collective, individually and as a unit.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

The stress and pain that both the Overture staff incident and the defacing and theft of a fellow artist’s work was detrimental. Not only the events but the absolutely incompetent and disgusting, disrespectful response from Overture and MMoCA. The passive responses we have received continue to demonstrate exactly what the show and artists worked to cry out against with our work. We again as black women/gnc persons feel invalidated and tokenized. There has been no apology. No explanation. And now silence for weeks. I continue to worry about my artwork on display as it is interactive and therefore in danger.

Martina Patterson

Martina Patterson is an artist, master naturalist, herbalist, and environmental educator. Through her art, fiber, and eco-mixed media, she attempts to explore, share, and emanate the loops and patterns that define connections with the intent to grow, inspire, and educate. For over 7 years, she has served as a volunteer, artist, and community organizer for FLOW–a rural/urban consortium of artists, farmers, and creatives. Some of Patterson’s most recent collaborative artworks can be viewed on The Great Sauk State Trail and at Baraboo Middle School. Recent nature projects include trail building and future land restoration in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as well as transplanting apple trees from Sauk County—Maa Wakacak (Ho-Chunk Sacred Earth)— near Baraboo, Wisconsin, into Havenwoods State Forest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

To showcase collaborative works with my Ancestors that inspires, educates, and evokes dialogue around Black Female/Femme Art/Artists; our necessity; our brilliance. To Share my grandmother’s artistry and skill that was always overlooked.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

1) The tenacity, the brilliance, the beauty, the LOVE, the POWER of being a Black woman.

2) Although I am supported and celebrated in my circle; I am still invisible to the majority.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

This has been discouraging, in that invisibility is exhausting. It has been encouraging, in that my Sistars never cease to pull up. Love is real despite the evils and outside bullshit.

Nia Wilson

Nia Wilson is a multidisciplinary artist and storyteller. She received her BA in Studio Art and Journalism from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in spring of 2020. Her artistic explorations span from fibers, video, painting, photography, and sculpture to poetry and narrative forms. In 2018, she studied abroad in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and received an internship at the Institution of Afro-Brazilian Research and Studies, an institute aimed to preserve, research, and educate around the Afro-descendant culture in Brazil and keep the legacy of the late artist, Abdias Nascimento. Wilson has worked with Community Arts organizations within Milwaukee, such as Artist Working in Education. Currently, she has a fellowship at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in the Education Department. Wilson has exhibited her artwork in multiple venues throughout Milwaukee.

Photo by Andrea Waala

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose for being in this show was to showcase a voice and representation of myself, my Black community, my family, my identity as a black woman, and my culture. But also to share space with my fellow black artists who have rich and amazing artwork to share. I wanted to show how Black art is simply amazing and phenomenal art.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The show means a lot especially in this racially and socially divided state as Wisconsin. It was truly a voice that highlighted black artists across the state. My first time showing my work as an artist in a museum. I expected more…truly disappointed in MMoCA on how we have all been treated and discriminated against because we are Black.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

It’s been terrible. Words can’t describe how disappointed I am with MMoCA. Shame on you all for how you treated all of us (artists), especially Lilada Gee and our curator Fatima. No way this would have happened if we were white.

Rhonda Gatlin-Hayes

Rhonda Gatlin-Hayes is a self-taught artist. Upon her mother’s death, she inherited a multitude of sewing notions, buttons, fabrics, and crafting items. Inspired by the idea that these broken, devalued, disregarded, or unwanted items could be repurposed and re-elevated, Gatlin-Hayes’ childhood creativity reemerged, resulting in detailed assemblages and collages. Her whimsical, but lifelike, artworks incorporate fabric, leather, beads, glass, wood, screws, nails, buttons, wire, metal, shells, rocks, minerals, bone, string, paper, and feathers—uniting unlikely objects to show the beauty in their differences. Celebrating the strength of the human spirit, she creates representational masks that depict and carry the message that everyone has worth and that no one should be taken at face value; everyone should be looked at more closely, for what lies beneath.

Photo by Phyllis Bankier

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose for participating in the show was to celebrate my femininity, individuality, self–worth and African heritage paying homage to my ancestral mothers and sisters. This has also afforded me the opportunity to participate in a sisterhood that is rarely given the same level of exposure as that of women of other ethnicities.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The Curator’s design of the show was outstanding. The opening of the show was epic. It was amazing to see over 500 black and brown individuals in one space celebrating Black women artists along with our works and collaborating to establish future opportunities where Black women can be recognized for our accomplishments and endeavors.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

The racial discrimination of Lilada Gee with the Overture Center did not only cause trauma for the individual artist, but it brought to my remembrance of times in my life when I was discriminated against because of the color of my skin. Subsequent to that incident, the artist’s works were vandalized within the walls of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art where the works were to be safe and given the same level of importance as the Museum’s Personal collection. A non-urgent response from the Museum regarding the vandalism mirrored the actions of the Overture Center regarding its employee act of discrimination toward the artist (Lilada Gee).

For me, this is another form of slavery. It is mental anguish and emotional abuse which is as taxing as physical abuse.

Rosemary Ollison

When Rosemary Ollison was 16 years old, she moved to the Midwest from a plantation in Arkansas. A self-taught artist, she began making art in 1994 while healing from an abusive marriage. For the last three decades, Ollison has explored numerous media in her work. Her work reflects her identity as a Black woman and celebrates the power, individuality, and mystique of other women. Besides drawing, she collects glass, leather, bracelets, beads, bones, and jewelry and repurposes these materials into sculptural works. She has redesigned her small apartment with layers of pattern, duct tape sculptures, curtains of woven leather, crazy quilts, and inventive drawings. Ollison also designs clothing and writes poetry.

Photo by Lois Bielefeld Society Portrait Gallery

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

My purpose for participating in this show was to support Fatima Laster, a young Black woman that I highly respect and admire for her accomplishments. Also because of the opportunity to work with those I know personally and get to know so many new beautiful Black women and their awesome works.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

This experience has been very disappointing to me. But has not influenced my determination to be the wonderfully made Black woman that I am. “AIN’T I A WOMAN?”

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

As regards the museum, I need more time to think about the whole situation.

Ruthie Joy

Ruthie Joy is a self-taught visual artist and graduated with a BA in Psychology from Alverno College. Her works are saturated with bright colors that flow across various mediums, including canvas, paper, ceramic, and glass. She experiments with used coffee grounds which, when combined with acrylic paint, allow her to create a heavy multi-dimensional texture on her pieces. Joy uses her art to express the significant role of hair in defining the identities of various cultures, particularly African Americans. She uses her own hair as an integral part of her art to add depth and authenticity. Joy has exhibited extensively, including Women of Creativity at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in 2020. In 2019, Joy was accepted into Milwaukee Artist Resource Network (MARN) mentor program.

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

The fact that I was asked to be a part of this show was a very humbling experience. I Was looking forward to celebrating with this group of talented Black Women, to show why we are great women who are just as creative as our counterparts. To have a curator with such instinct was phenomenal.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

This was the most amazing Sight to see Black women showing their work being honored which most likely has not happened in a white institution such as this, we are a threat in their eyes. We are Black Women who went in on this task with Tenacity to show the power that we Possess.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

I had to think long and hard over this because I was under the Illusion that the stress did not impact or affect me in any way whatsoever. I was wrong, I was doubting myself as an artist. Am I good enough to compare to white artists? This was supposed to be a celebration but in the end it is a frightening image of the past, in which racism is showing its ugly head.

Sharon Kerry-Harlan

Sharon Kerry-Harlan is known for her textile works, paper collages, and paintings. Her work explores elements of her ancestry while resonating with a clear understanding of both the chaos and the order of modern, metropolitan life. Kerry-Harlan moved to the Midwest as an adult, where she graduated from Marquette University. In addition to working as an Academic Coordinator at Marquette University, she taught textile and quilting courses as an adjunct professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. At the same time, she began taking classes at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, developing her body of work alongside her professional career. Now retired from the educational field and focused full-time on making art, Kerry-Harlan continues to create and experiment with fabric manipulation in her characteristic mixed-media and painted works. Her works have been collected and exhibited by museums across the country and internationally.

Photo by Randall Harlan

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

For many years, I visited the Wisconsin Triennial at MMOCA. As I always do when I attend exhibitions, I took note of the artists of color who were chosen for the show. Like most museum shows, there were always very few artists of color. The 2022 Triennial for me was to be a barrier breaker. An African American women curator and an extensive list of accomplished women artists in the Wisconsin Triennial, I absolutely wanted to participate.

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The 2022 Triennial’s focus on Wisconsin African American women artists was genius and timely. It was an opportunity for the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art to separate itself from art institutions that continue to devalue the works of people of color. The featured works in the exhibition were strong, relevant, and inspiring. The works prove what we already know, Black Women are brilliant.

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

I am shocked and dismayed that we (the artists) find ourselves in this depressing situation. What was to be a celebratory exhibition is now mired in controversy. Unfortunately, the show is in a precarious position and the stress of the outcome is unsettling to us all. The joy of being a part of the 2022 Triennial has substantially diminished.

Portia Cobb

Portia Cobb is an interdisciplinary artist deeply interested in telling stories that reflect the double-consciousness of Black American identity, history, memory, and forced forgetting. Her body of work and research has joined these themes within short-form documentary video, digital photography, field recordings, collaborative installation, and community-engaged performance art. Cobb holds an MA from San Francisco State University and a BA from Mills College. She teaches at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the Department of Film, Video, Animation and New Genres.

Photo by Pat A. Robinson

What was your purpose for participating in the show?

I was honored to have been invited. This would be my 3rd Triennial, but for me the most meaningful because it was curated by an African American Woman and focused on the intergenerational works of Black Women and femmes/GNC-breaking with the traditional framework of the Triennial blueprint

What did the show highlight for you (as Black women, femmes, and GNC folk)?

The highlight was its feminist and intergenerational concept, taking on a call and response. It was reflectively organized/curated. This became evident when we all experienced the work as an ensemble in the spaces it occupied. Many of the spectators remarked on the color themes, graphic and overall design. This made it unique, meaningful, evocative, and mirrored our kinship as Black women creatives

What has the stress and impact of this experience been like?

From the jump, receiving information about the treatment of Lilada Gee by the Overture staff person and the interruption of our collective joy and again in the aftermath. The turn of events and the silencing of any open discussion, panel or public discourse has been fatiguing.

Many of us have expressed how worn down we feel. Emotionally and psychically depleted.

A glimpse of the potential for hostility occurred a few weeks after our opening, when I stood in the gallery with a visitor that accompanied me to Madison. I overheard condescending remarks by a white woman, who closely fit the description of the “Madison Beth” Lilada had so accurately captured in her performance reading. This person openly made a condescending remark about the matrilineal quilt that hung in front of the Sojourner Truth Graphic, which was part of artist Martina Patterson’s installation. This remark was shared with the gallery attendant, and anyone in earshot. I was standing a few feet away in front of my own installation at the time. This woman questioned the validity of the quilt having any artistic value and suggested that if MMoCA considered this “art” she had a “bunch of old quilts” she could donate!

Witnessing this, my immediate response was “Wow! This is the hostility that Lilada described.” And my second reflection about it was that this show really was doing its job — because it was making some folks uncomfortable.

I think it is a shame that we as individuals have had to grapple with the possibility that our art could also be vandalized, dis-respected, not held to the same standards as the work a floor above. I am sorely disappointed in the cowardice of MMOCA’s management and board. It is disconcerting that they remain mute as 7 or more artists have asked for their work to be deinstalled and returned.

Where are the protections that are shown other exhibitors?

The lack of a public apology and the paltry excuse that the director stated in a media source about postponing a public discussion to allow those who were harmed to heal. This is absurd. It is clear that Christina Brungardt, the Director, has washed her hands of any responsibility surrounding the assault, lack of security and protections leading to the defacement of Lilada’s art in the exhibition.

Our collective Black female, femme, gender non-conforming bodies continue to bear the brunt of the labor; the labor of amplifying our concerns and these events beyond Madison. We are charged with the labor to protect our dignity and our right as artists to hold space in this historic Triennial. And now with the weight of documenting this critical experience so that it isn’t swept neatly into a folder and forgotten.

Because my work has a media component, my struggle from the onset was the lack of care given to make certain it was accessible, heard the night of the opening, and properly documented.

The stress of protecting the curator — no matter what — and holding MMOCA and the Director accountable.

The stress of taking next steps to make a request to remove work from this exhibition under these conditions.

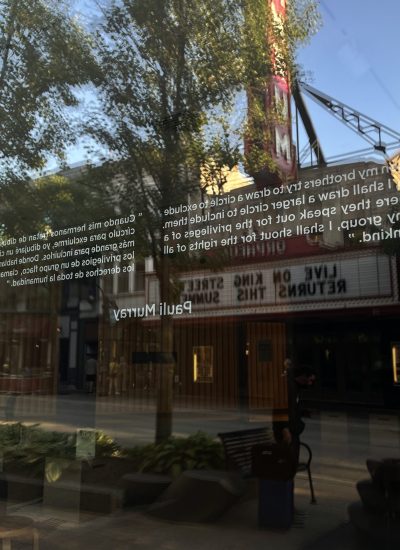

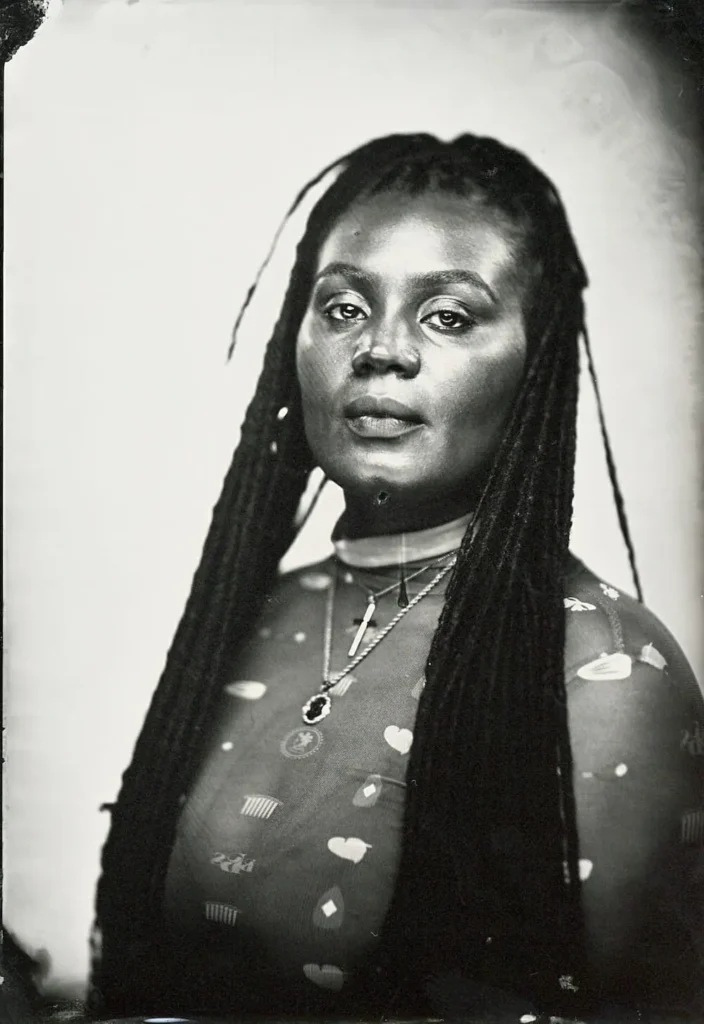

Nakeysha Roberts Washington

Nakeysha Roberts Washington is a performance and published literary artist. She received an MS Ed and has 13 years of experience as an educator in secondary and post-secondary institutions working in areas of literature and writing, curriculum, and instruction. She is the owner and Creative Director of Genre: Urban Arts (GUA)—where creatives can grow their skills through workshops and courses, become published, showcase art and multidisciplinary works through exhibitions, and flex one’s performance skills at organized pop-up events. GUA also serves as an educational consultant group to develop literacy and arts workshops that center upon culturally responsive practices, anti-racist/anti-biases philosophies, and social justice topics. As an artist, Roberts Washington recently performed a monologue in Brooklyn, New York, at the Billie Holiday Theater as part of a showcase entitled 50 in 50: What Place Do We Have in this Movement?

Photo by Nakeysha Roberts

As her impact statement, Nakeysha Roberts Washington offers the email sent to MMoCA and Christina Brungardt requesting to withdraw.

This letter is published alongside the wall label installed to indicate the absence of her artwork.

Hello everyone.

I am writing to let you know that I am requesting that my art be removed from the exhibition. I am also not going to move forward with the design of the newsletter. I was really excited at these two opportunities to showcase my work, but I cannot move forward knowing the sheer disregard and disrespect of Lilada’s work by the museum. This experience has caused me a lot of stress and anxiety and all the joy that it held has been exhausted, replaced with the nagging feeling that I was never truly welcome. I do not want anything I do to be tokenistic and endeavor for all collaborations to be in spaces where me and people who look like me are well and easily respected. I do not see how this matter can be rectified, as the damage is already done.

Additionally, I would like the responses to my questions on the purple papers to be sent in an envelope with my installation as well and for the question signs prompting responses to be removed from the space.

I would like my work shipped to [X] by July 29th, 2022.

In addition to the removal of my work, I am requesting that the attachment to this email be placed on the wall where my installation was placed until October 9th, the closing of this exhibition.

Sincerely,

Nakeysha

Nakeysha Roberts Washington, email message to Christina Brungardt and MMoCA staff, July 18, 2022, 1:57pm (CDT)

Tanekeya Word

Tanekeya Word creates multimedia visual art such as paintings, drawings, prints, and book art. Word earned a BA in English and Afro-American studies from Howard University, and studied painting under James Phillips of AfriCOBRA. She holds an MA in arts management from the American University and is currently an Urban Education dissertator, with a specialization in Critical Race Theory in Art Education. Word’s forthcoming dissertation is entitled Black Womanhood + Black Aesthetics in Art Education. She has participated in national exhibitions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Koplin Del Rio Gallery, Seattle, Washington; and HighPoint Center for Printmaking, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Her work is held in several private and public collections, including the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts; and Milwaukee Art Museum, Wisconsin.

Photo by Margaret Muza

On Wed, Jul 6, 2022, 4:23 PM, from Tanekeya Word:

SUBJECT: Re: Gallery closure

Leslie,

Thank you for reaching out to us on behalf of the museum. I am Tanekeya Word, one of the artists that will have work returned. I agree with you, there is no wrong or right for the decisions the artists or curator decides to choose.

Yet, I hope that Christina has shared with you the varied concerns of each artist and curator involved. Unfortunately, there has to be more reciprocity beyond operational shifts. The ask for Black women to stick it out for the community when they’re harmed is regressive, patriarchal, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s kind of feminism and oppressive to say the least. Historically, suffering has often been the only option for Black women–to care for others in the exchange of the detriment to their spirits and bodies. We are our ancestors’ wildest dreams, right here, right now.

MMoCA has undermined the trust of Black women, upheld white privilege, not given our artwork the care and attention it deserved after the initial assault on Lilada Gee. We moved ahead, after apprehension, and a second assault occurred in the same locations: geographically and systemically. From an assault on the Black body and spirit of our sister Lilada Gee to an assault on Black artistic cultural production and spirits. The operational measurements outlined in your email are basic and should have remained a core line item within the exhibition budget knowing the carceral space our bodies and our work would enter. How are we being offered basic exhibition security measures months after the opening?

It’s not our duty to be Ruby Bridges and our other foremothers to bridge the etic community outreach of an institution who is eager for a visibility quota or grant measure rather than to understand authentic equity. We are more than a measurable, we are more than a photo opp.

I’m full of gratitude that you reached out, but it’s also unfair to have you on the front line when it’s not you or us who need to enact change. A Black man, a peer is inquiring if we can sit back to reassess pulling out of an exhibition that does harm to us, but uplifts an institution for making change by exhibiting the works of Black women. On the outside it looks good and often power and autonomy is exchanged for visibility. I question the ethics of anyone who thought it was a great idea to put another Black body on the frontlines of a white institutional disaster. Not your mess and not our mess to clean up.

So, my inquiry is after all of this turmoil what has each Black woman artist and curator involved gained but more trauma?

No artwork is being acquired for a permanent collection to ensure a longevity of on view exhibitions and programming that creates a legacy within the institution on emic narratives of Black women. No paid programming was established with Black women for the exhibition outside of an exhibition and curatorial stipend that was matched based on the initial assault.

There is not enough on the table to repay for the suffering and to repeatedly allow more harm so that an institution who has the culture of upholding white privilege looks good to the community it serves and let us be very clear–that community is not Black women–yet, our backs should be the bridge.

Honestly, I am in awe that the damage and insults keep coming. How much should a Black woman or femme bare?

In Truth + Service,

Tanekeya Word

LaNia Sproles

LaNia Sproles’ body of work spans several disciplines, including printmaking, drawing, and collage. The philosophies of self-perception, queer and feminist theories, and inherent racial dogmas are essential to her work. She examines the works of feminist artists and writers such as Octavia Butler, Rebecca Morgan, and Kara Walker. Sproles graduated with a BFA from the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design in 2017. In 2020, she completed her year as a 2019 Mary L. Nohl fellow, continued as a teaching artist-in-residence at the Lynden Sculpture Garden, and guest curated an exhibition hosted by NADA art fair with Green Gallery.

Photo by Laura Dierbeck

Maxime Banks

Maxime Banks is an award-winning, interdisciplinary artist, and a time traveler of the Black American Diaspora with Illinois, Louisiana, and Mississippi roots. Her praxis intersects science, visual art, technology, and design with otherness sensations across Afrofuture anamnesis, collage, writing, poetry, textiles, and painting. She composes self-portraits as documentary constellations of her journey as a Black American woman emigrant to Europe and then to the Southern Antipodes. She translates quantum entanglement, quantum tunneling, and subatomic particle ghosts as metaphors of Black alienation, Blackness ontology, and Black Joy. Banks received her BS and BFS (Honors) from universities in the United States and Paris, France. Her MFA postgraduate research study is at the University of New South Wales/UNSW Art & Design, Sydney, Australia.

Photo by Astrid Mbani

Ariana Vaeth

Ariana Vaeth is a Baltimore-raised artist focused on contemporary personal narrative through the self portrait. A graduate of the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, she completed an exchange program at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Vaeth has exhibited at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, Wisconsin; the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Terrault Gallery in Baltimore, Maryland; and in Chicago, Illinois, at the Woman Made Gallery and the Museum of Science and Industry for Black Creativity. Vaeth is the recipient of several awards and accolades, including being named a Mary L. Nohl Fellow in the Emerging Artist category, two Gener8tor.Art grants, and the 2020 Wisconsin Visual Art Achievement Award.

Photo by Taylor Belmer

We stand in solidarity with all impacted artists. This page will be periodically updated with additional statements and signatures.

Bios, portraits, and other information about the 2022 Wisconsin Triennial Exhibition artists, as it appeared on the MMoCA website, can be found here.

This project is dedicated to Lilada Gee and Fatima Laster, who have demonstrated great strength and grace when they should not have had to.